Image: https://www.londonproperty.co.uk/en/the-history-of-london-boat-race/

Learning together and learning from each other is incredibly important – no single person can know everything there is to know on a particular topic and the process of reflecting together can broaden and shape our understanding profoundly.

A great example of this happened last week when I met up with two colleagues from a partner organisation who have also become friends: Gail and Sam. I have known them both for a couple of years and at different times we have talked about the work we’re involved in and how it overlaps with each other. We’d met together to talk about my research internship and what I’d learnt so far…the conversation roamed around as these things do, and we ended talking about PPI more generally.

I explained that one of the academic papers I’d been reading suggested that there were over 60 ‘frameworks’ for PPI (1), each of which had been written by a particular team in a particular context. The only cases where these frameworks had gained any traction appeared to be when the authoring team had pushed hard to promote it amongst their colleagues and in their clinical area, but it hadn’t really been adopted beyond that space. Other papers (2) discussed the different imperatives or reasons which motivate researchers to do PPI: there’s the moral or emancipatory reason: patients have the right to be involved in decisions and research which will affect them and their involvement challenges power-imbalances. A second reason is efficiency and pragmatism: involving patients brings additional real-world knowledge through lived experience. The third reason is political and practical: forming alliances and partnerships with patients and carers reflects the more modern scientific view which recognises that knowledge can be created both inside and outside a research institution and that by involving the public, research becomes more transparent and accountable.

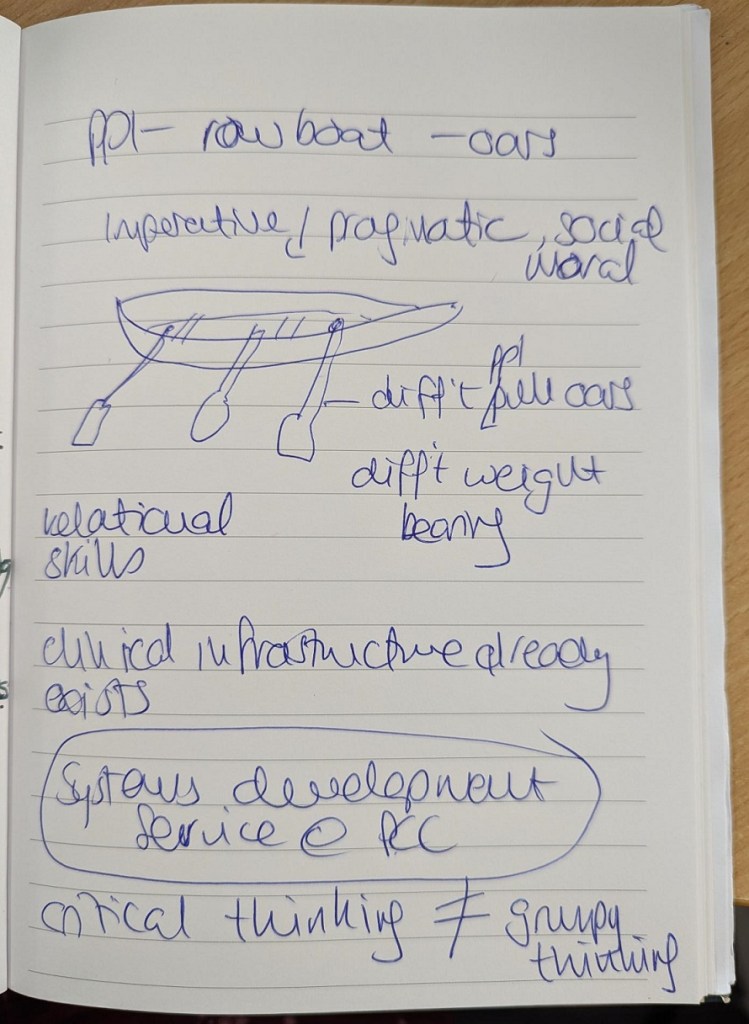

All of that is about why people might choose to engage with the public. But it still doesn’t really articulate the how we do things the way we do part of the job. As we continued talking, I began to make some notes and sketch out my thoughts*

*I’ve come to realise that part of my ADHD reveals itself through sketches, analogies and metaphors. I use them to ‘illustrate ideas’ and articulate how I make sense of complex problems or issues.

There’s lots of information available, both academically and anecdotally, about how PPI is done and as we were talking, the idea of a row boat came to mind which seemed to encapsulate all of these seemingly disparate elements.

We have lots of guidance about the practical “how to’s” such as PPI payments, ensuring ethics are covered etc. The Health Research Authority recently published 19 recommendations for system-wide change to support people to take part in research or to improve clinical research for participants. We could think of this as how to build the boat; the mechanisms needed to contruct it. The practical things of: you need this many people, you need to pay them, you need an Ethics form, and things like that. And I think that the assumption is, that if you have all the correct components in place, then somehow, it will just work…?

However, the boat and the effective functioning of the boat is based upon relationships and the skills to develop relationships – communication, empathy, compassion, understanding different contexts, the understanding of power dynamics…balancing all of those things out, all of that is really important, but it’s not said out loud. Curiously, there seems to be an assumption that somehow researchers (or even PPI Leads) will know and possess these skills, even though it’s not covered in academic training. Thus – there’s a danger that without that understanding, people manage PPI – and by extension public contributors – like the’re a component in a project, like lab resources or data analysis, but not in the way that people need to be supported and managed.

The boat is the combined effort of people working together in order to design and deliver a research study. The boat frame (the wooden part if you like) provides the technical framework for how people could work together (the rules and guidance about PPI). The imperatives I listed earlier (moral, practical or political) are the reasons why people might want to get in the boat. But the boat isn’t looking at the study or the project from a clinical point of view, or a technical point of view, it’s looking at it from the PPI perspective.

And the analogy keeps going: there are different people in the boat – there’s the Principal Investigator (the person with overall responsibility), the Clinical Advisor or Medic, there’s the Data Analyst, Pharmacy team, a PPI representative, a Research Nurse and many others. All of those people are in the boat and they are rowing together but they may not all be rowing at the same pace. They may not all have the ability to pull on the oars consistently and that’s fine – the Principle Investigator or Lead Researcher just need to understand that and be aware of it.

As people are added to the boat it needs to be balanced, rather than having all the weight at one end. If one person is pulling two strokes and another person’s only doing one that works so long as they’re both in sync and they’re not clashing. You can manage that through the relationships that are built in the boat – the exploration, the discussion, understanding of expectations of those different roles; what different people are bringing, what they’re expected to bring, what they have capability to bring… otherwise all the oars might end up clashing. This is where the power-imbalances and reciprocity of PPI in research comes in. (Reciprocity means that the project is beneficial to everyone involved, in whatever way suits them best.)

However, sometimes this can fail spectacularly, particularly when it comes to Public Co-applicants. Let’s imagine the row boat is in the water and it’s travelling a little way along because the clinical team have started with the study design, for example. And then they think, “Oh gosh, we need a Public Co-applicant, because that’s good practice.” So as the boat rows along they spot someone on the dock. They pull up and see someone there who says, “I think I might like to get involved in research.”

The team are so pleased to have found a willing partner, that they pull them into the boat straight away! The Principle Investigator says: “Sit there, and hold that,” pointing at the oar and off they go! But they don’t tell them where the boat is going. They don’t tell them what to do with the oar. They don’t teach them how to row in sync with other people. So, the person is left there sitting on the bench holding the oar and thinking: “Well, why am I here? What am I supposed to be doing? How am I contributing to this?” and they feel discouraged and somewhat redundant. This is a classic example of tokenistic PPI, where the poor co-applicant is dragged in because somebody thinks: “Oh, we’ve got a space in the boat, we really ought to have a PPI rep,” without giving any thought to why they’re in the boat and what they want them to do with the oars…! This is a key area where PPI can go wrong because researchers might not know how to support relationships with Public Contributors and what they can reasonably ask of them. Again, nurturing those relationships and communication skills is crucial if the study is going to be set up to succeed, rather than fail.

Something like Social Pedagogy could teach people how to row as a team: things like communication and rowing in sync and having that shared vision. But that’s the bit that researchers aren’t taught. They’re taught all about the mechanics: how to build the boat, how much wood you need? How many benches you have to have, making it watertight (or hoping it’s watertight!) The guidance talks about how many rowers you need, how many oars you need but they’re not taught about how all of that works together in order to function.

So that’s the PPI boat with all its’ complex nuances!

What do you think? Does that resonate with you? Does it reflect your experience? Is there anything missing? Do share – I’d love to hear from you 🙂

(1) (2) Frameworks for supporting patient and public involvement in research: Systematic review and co‐design pilot. Greenhalgh et al 2019 https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12888

Leave a reply to Values, not just systems – Authentic PPIE – the (re)search for authentic engagement Cancel reply