Image: https://autistic.blog/2023/04/21/the-social-contract-2/

I’ve been supporting one of my volunteers recently and it’s sparked a whole host of thoughts this morning about trauma-informed practice and unspoken social contracts. This may not appear directly relevent to PPIE work, but as we explore this thread, hopefully you’ll see the links.

The individual I’m supporting has a number of physical and mental health conditions that they’re living with. This makes every day a challenge in terms of engaging with people, services and managing symptoms. Recently they’ve had moments of crisis and sought help from the NHS. Unfortunately, the staff they met didn’t fully understand their condition or the help they needed and instead of helping, it made the situation a lot worse.

We’ve been emailing to and fro and they wrote to thank me for showing trauma-informed leadership. I’m actually very interested in trauma-informed practice and I don’t feel that I know very much about it, so I was both grateful and humbled that they felt that way. I’ve been looking into some online training to get me started in this area and it sparked a host of thoughts…

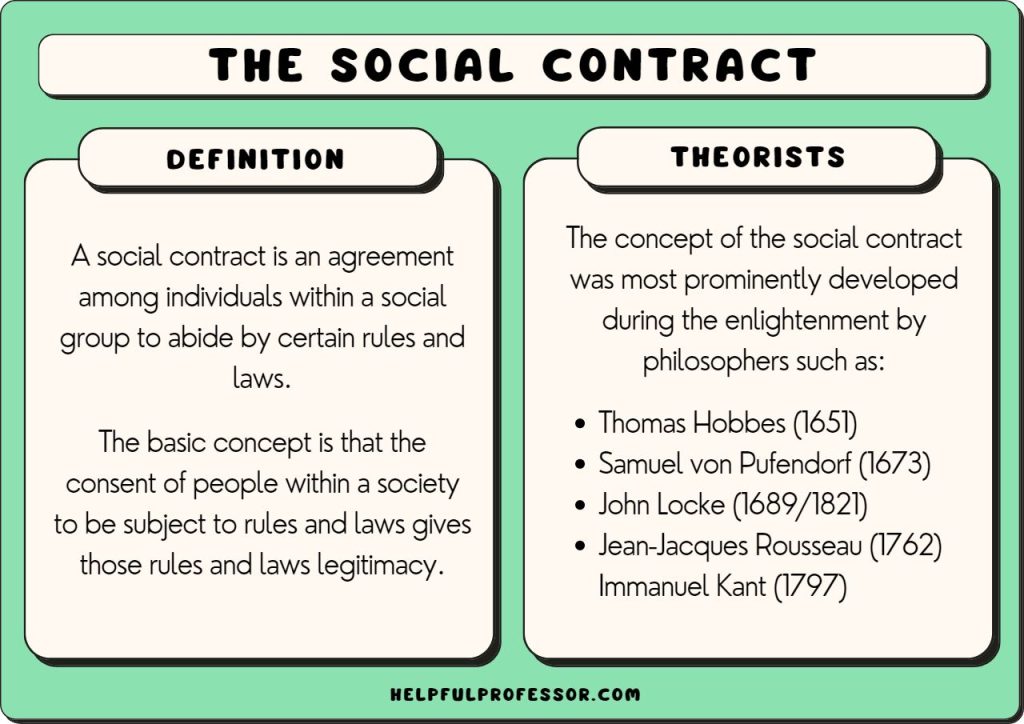

It occured to me that if I access support from public services i.e. if I go to my GP, the Housing Office, or ring a crisis line or take myself to the emergency dept, I’m engaging in an unspoken social contract, and it looks something like this:

I give you something (I make myself vulnerable, and take a risk by giving you information and sharing things which I find difficult, embarrassing, shameful, debilitating…)

You give me the help I need (acceptance, support, validation, flexibility, understanding)

Now when it works well, this unspoken social contract does exactly what it should: I give you the information you need to help me – and you help me. Perfect. But when it doesn’t work well, that exchange can be incredibly harmful. Instead of receiving acceptance, validation and support, I get:

blame – you should have done XYZ instead*

suspicion – you don’t look that ill; you seem fine to me; you’re coping perfectly well in this appointment**

disinterest/excuses – I can’t help you because your needs don’t fit our system; because you’re too specialised/niche/unfamiliar; because we haven’t got funding; because I don’t really understand what your problem is

Now, instead of feeling supported and finding a solution to my issue, I feel shamed, embarrassed, inadequate and a failure. What should have been a positive experience, has made me feel worse – plus someone else knows about how much I’ve been struggling and how bad I feel, and has shown me no compassion. It’s somehow my fault.

It’s also important to point out that I have taken a ‘risk of trust’ – that is to say, I have taken the risk to trust you (the practitioner) even though I have no evidence yet that you are trustworthy. I’m trusting your role/job title/area of responsibility to help me, even though in any other context, trust has to be earnt and proven. As my Mum used to say: Trust is hard earnt and easily broken.

This is where trauma-informed practice becomes essential, because if you as a patient or service user (or some other appropriate phrase) go through this process a few times and have negative experiences, you could come away feeling like your situation is entirely your fault and you don’t deserve help, because all your experience with practitioners to date has simply underlined that belief.

The unspoken social contract has been broken.

In my limited understanding, it seems a great deal of trauma may have come into being where people in crisis have sought help and been met with a negative response, leaving them not only remaining in crisis, but now struggling with additional feelings of shame, vulnerability and failure. Moreover, the likelihood of that individual being brave (again) and asking for help (again) gets less and less every time. Why should practitioners expect members of the public to trust them, if that trust has been repeatedly broken?

I’ve been doing some free online training through the Open University recently, looking at trauma-informed practice and one of the contributors, an Assistant Director of Children and Family Services commented:

“How do you understand behaviour as a form of communication?…How do you help people articulate themselves when they may not have the language for it?”

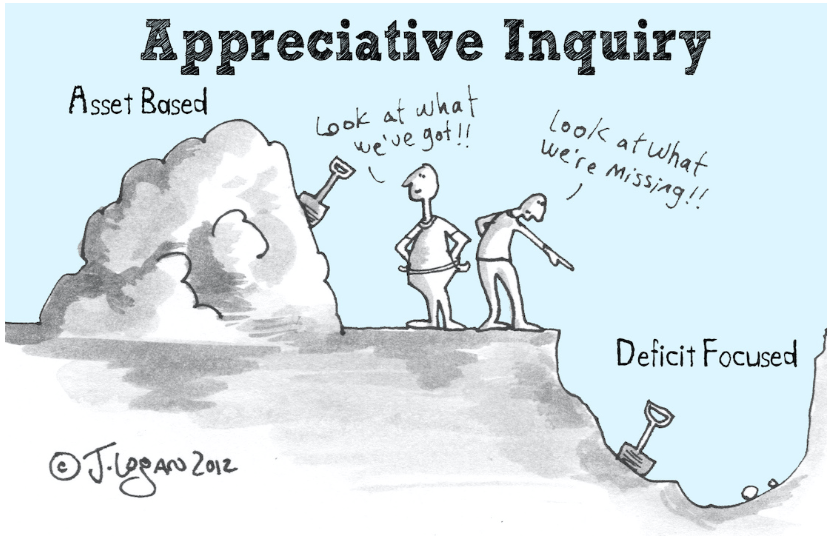

Engaging with people in a meaningful and positive way might require using all our senses and interpretation skills, to listen, articulate and reflect back to the person we’re listening to – to check that what we’re hearing is what they’re trying to say and then offer help on the basis of that exchange. We can’t promise to solve everything, but we can give some good reasons why that might be and support people to get the help they need. Honesty and transparency goes a long way.

So how does this relate to PPIE? Well, in a couple of ways:

First of all, when public contributors share their lived experience with us, it has the same importance and the same impact as the person coming to their GP, or attending the emergency dept seeking help. They are sharing things which are personal and life-shaping. Things which may make them feel vulnerable, which may make day-to-day life challenging. Information shared by public contributors for research should be held with the same regard as information shared with any practitioner.

Secondly, there is an unspoken social contract in place between researchers and public contributors – although researchers may not always know that. It looks something like this:

I give you something (I take a risk and share personal information and experience which may or may not be challenging for me)

You give me something (You value and respect the information I’m sharing by giving updates and information about your research, so that I can see how my vulnerability has contributed to your study and helped make things better for others)

Again, when this works well, it’s brilliant: research participants and public contributors feel valued and validated and perhaps even more importantly, they’ve found some purpose or meaning in their experiences.

But when that unspoken social contract is broken, people feel used, devalued, dismissed and maybe even dehumanised. And the likelihood of them ever supporting research again in the future is much reduced.

I need and want to do a lot more study in the area of trauma-informed practice, because I can see it’s an essential part of my toolkit for working with underserved and vulnerable communities. The step after that will be helping other practitioners and researchers see how and why it might be useful…

*This issue of victim blaming was raised in a different context recently, in an article in The Guardian. The journalist was talking about their experience researching the Metaverse and how they were virtually sexually assaulted in that space within 2 hours of being there. A female beta tester reported similar behaviour: “After Meta reviewed the incident, he claimed, it determined that the beta tester didn’t use the safety features built into Horizon Worlds, including the ability to block someone from interacting with you…the immediate shifting of the blame and responsibility on to the person who experienced the abuse – “she should have been using certain tools to prevent it” – rather than an acknowledgment that it should have been prevented from happening in the first place.”

** It’s worth pointing out that someone may appear to be coping because of a drop in cortisol – the relief of getting an appointment and the hope of getting some help may lower the stress and anxiety levels temporarily, making someone appear to be coping better than they are

Leave a comment