image: https://www.rubi.com/en/blog/how-to-build-a-brick-wall-step-by-step/

Back in March ARC South London put on a webinar about Emotions in PPI. I signed in to watch it at the time, but on that particular day I was being battered by perimenopausal fatigue and could barely function, so I sidled out again and vowed to watch it on another day.

Well, today was that day and I have to say it was a cracking webinar! I’m really glad I gave it another shot!

The webinar was about emotions in PPI work and focussed on some research carried out by PenARC which is the Applied Research Collaboration for the South Western Pennisular which covers Somerset, Devon, Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly.

The presentation took us through the origins of the research and the findings from the conceptual review they did with public contributors, to see whether there were any existing papers on emotions in PPI work. It was a really interesting and interactive session which is really well captured in this follow-up article which includes the interactive Word Cloud responses from attendees.

As I was listening to the comments and questions after the presentation, it occurred to me that emotions are what motivate us. They are our instinctive response to information, whether that information is presented as numbers, words, sounds or visually. In Ancient Greek philosophy, emotion was often portrayed as the enemy of logic and whilst it had it uses, it wasn’t necessarily viewed as the best guidance for decision making and living a well balanced life.

This is view is still very prevalent today, with emotion and emotional presentation being sometimes described as ‘an outburst’, ‘erratic’, ‘over sensitive’, ‘unreasonable’, ‘unstable’ or ‘dramatic’. Whereas someone who doesn’t express emotions in an uncontrolled manner might be said to be ‘calm’, ‘in control’, ‘sensible’, ‘composed’, or ‘disciplined’. It’s not hard to see the negative and positive spin on those words.

But emotions aren’t necessarily bad – far from it. As a teacher and youthworker, I know that emotions in children and young people are very healthy. As I have said many times it’s not the emotion that’s the problem, it’s what you do about it. It’s actually very healthy to be angry if someone has hurt or betrayed you – the issue comes with whether you confront them with words – or a chair.

In contrast, repressing emotions can be equally harmful to the individual holding them. Unprocessed emotions or experiences can manifest themselves in other ways, often through physical symptoms such as persistant headaches, muscle pain and other symptoms. This video is an excellent summary of the book The Body Keeps the Score which explains this phenomenon in more detail. It’s fair to say that the book is pretty long and contains some complex and potentially traumatising case studies, so if you’re looking for advice in this area you could try this list from Root to Rise Somatics or this one recommended by readers on Goodreads.

So if emotions are healthy, how do they or should they feature in research – which holds itself as being impartial and objective? Surely emotions are not at all impartial or objective, so they shouldn’t feature in research or PPI?

I think in practice, it depends a bit on the context. If you’re doing discovery science in a lab, for example, then I think objectivity is essential. Bacteria or genes don’t have emotions or opinions about things – they simply complete their function and as scientists, we observe those functions and try to understand them better. We might get frustrated about the outcome of a failed experiment, but the bacteria on an agar plate arguably won’t really care one way or another.

However, if we’re weaving lived experience into that experiment – e.g. how well does this bacteria respond to this treatment and what side effects does it produce – then emotions can be a factor in this, because it will have an impact on how the patient feels and responds to that treatment. If the treatment causes headaches for example, but it works, then patients will probably be more open to taking it, provided they can cope with or treat the headaches. But if it causes headaches and doesn’t make any noticeable difference, then I think it would be hard to persuade people to keep taking it.

But this is still talking about science – what about PPI?

I’m going to take a side-step for a moment and talk about a project I used to be involved in called SIGHT. The title stood for Supporting Innovation and Growth in Healthcare Technologies and it filled a really useful space in the healthtech development market, helping very new or small businesses develop their product for market. I supported the team with PPI and I met with around 50 different companies who were in the midst of designing a diverse array of tech from apps to AI to clinical testing devices. Each time I met with a new entrepreneur I’d ask them to tell me about their product and each time without fail, their story was rooted in something personal. The event or experience which prompted them to start their journey into healthtech was always about something which had happened to them or a partner or family member.

It was personal because it was rooted in emotion and experience.

These individuals or teams were motivated because of something they had experienced and that emotion had stayed with them. They kept going because they believed in what they were doing. They wanted to make changes because they didn’t want someone else’s friends or loved ones to experience what they’d gone through.

Their experience generated an emotional reaction and that reaction created motivation.

When you ask a public contributor why they want to support research, the answers are often similarly rooted in experience and emotion:

“I wanted to give something back”

“The NHS was there when I needed them”

“I’ve received great treatment from the NHS and I want to help”

The conceptual review created by the PenARC team found that “emotion strenghtened the impact of what was being shared”. They observed that it “seemed to bring the group closer together” and that sharing emotions with people who had the same lived experience could be cathartic and a helpful way to process those feelings. Even if feelings were strong, that shared sense of vulnerability helped to build trust and a common purpose.

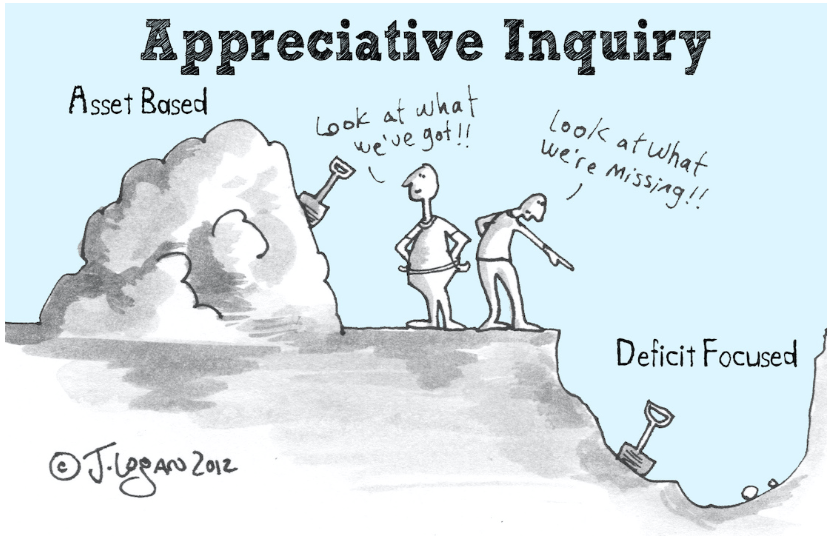

I think emotions are the mortar to the bricks of research: they are the glue, the motivating factor, the ‘sticky something’ which keeps the other parts stuck together. If no-one cared about improving the quality of life for people with Alzheimers, or cancer or failing hips, why would we bother doing any of it? Why spend all this time and money on improving healthcare if it doesn’t matter to anyone? Ignoring the economic argument for a moment, I think it’s actually the emotional one – how we feel about it – which motivates people more than anything else. After all, how we feel about something shapes our views and that affects our decisions and then our actions.

Without that sticky emotion-glue, there wouldn’t be as much motivation to persist, to innovate or to improve. If we were impartial, there wouldn’t be any kind of drive or personal investment to see things change….the bricks might be stacked tidily on top of one another, but it wouldn’t take much force to push them over into an untidy heap.

From the session on Emotion in PPI the issue seemed to be not the emotions themselves, but how they were handled:

How public contributors or people with lived experience were supported when sharing their personal stories.

How PPI Leads were supported (or not) having facilitated the meeting where all those things were shared.

How researchers were trained or mentored in how to work with people with lived experience, in a way which was thoughtful and respectful.

If good practice isn’t in place, then public contributors are at risk of being harmed; of having their trust broken; of feeling used and not respected. That’s why training for researchers and PPI leads is so important and why they also need supervision – a safe space to process what happened in the meeting and how they feel about it.

So do emotions have a place in research? Absolutely – especially in public involvement, but there’s some way to go before the much needed training and infrastructure is there to properly support it.

Leave a comment