Image: https://www.thoughtco.com/facts-about-sea-stars-2291865

Last week I had the opportunity to meet with two colleagues, Jenni and Kate, who also work in the PPI field. They are based at different organisations, but they encounter the same things I do in my work and I admire them both very much for their knowledge and experience. We’re planning to write an article together, with another colleague Mel, reflecting on the evolving nature of patient and public involvement. Unfortunately, Mel couldn’t join us for this initial planning session, so we put some ideas down and shared them with Mel later, who commented: “Wow, you don’t mess around do you – these are huge questions and quite brilliant ones.” The compliment was appreciated, but she was absolutely right: we’re not messing around.

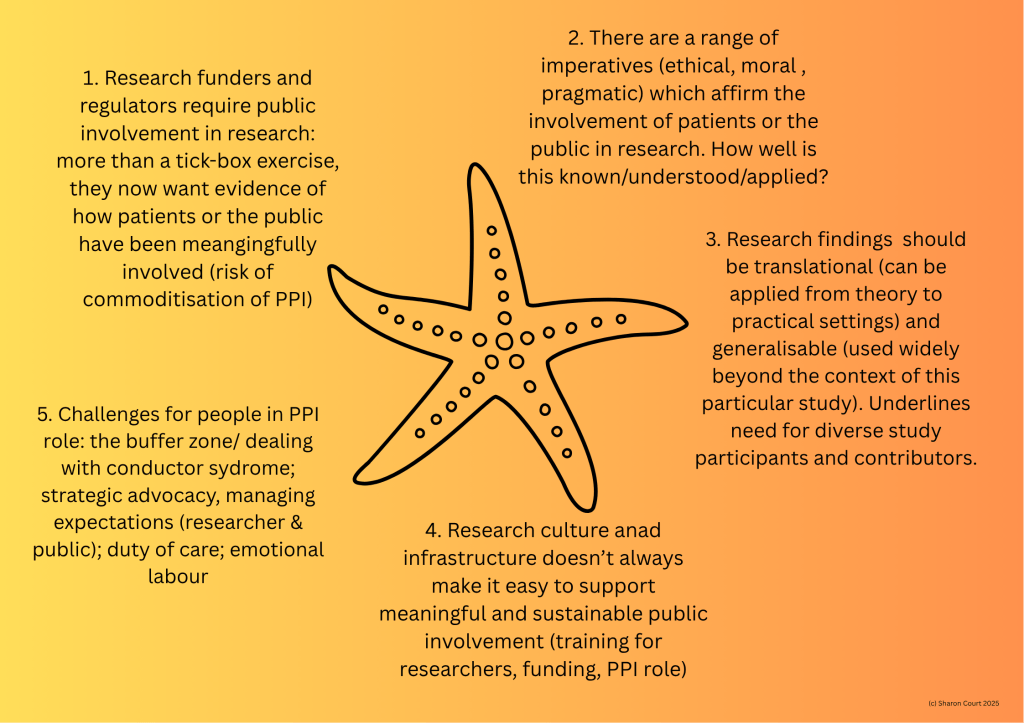

The field of PPI is evolving and there are some really challenging and uncomfortable

issues being raised by practitioners in academic, community and healthcare settings. These things need working through, but each one of them is connected to another one(s) (bad grammar but you get my point), which makes it tricky to unravel.

In short: it’s a starfish problem.

Starfish, as you know, have many limbs. We’re more used to seeing the Common variety which has five limbs, however other species such as the Sunflower or Crown of Thorns starfish can have far more than that. (If your curiosity has been sparked, this is a good website to tell you all things sea star related!)

If a starfish loses a limb, it can grow it back, although it’ll take up to a year to do so. Unfortunately, we can’t just hack off a limb from these interconnected problems and just ignore it – much though that might be more convenient! No, instead we need to take the time to work through both the individual problem domains (limbs) and the effect that they have on one another.

Whilst I don’t want to give away any spoilers for our article, perhaps this blog post might act as a ‘teaser trailer’ and give you a taste of some of what we might be discussing…This is my first attempt to visualise some of the interconnected issues which are impacting the field of PPI.

Truthfully, our PPI starfish needs more legs, or perhaps ‘sub-legs’ (legs coming off from the main limbs?) but hopefully at least you’ll get a sense of what I’m trying to convey without this becoming some kind of Cthulu-eque horror story?! These issues are not only connected to each other, but sometimes triggered by each other and therefore resolving them and making that solution stick needs a multi-faceted solution.

For example: there is a requirement from research funders and regulators that patients or the public are included in the design and delivery of research. This requirement has been in place for some time, but recently the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) issued guidance which insisted upon it. Professor Lucy Chappell, CEO of NIHR said:

“We are aware that researchers do not always build inclusion into their funding applications, and often it is a goal that is dropped, or not adequately resourced. While all applicants were previously encouraged to submit inclusive research proposals, we now require this to promote the cultural change needed to embed inclusion fully into the NIHR process once and for all.

“To do this we are applying the successful experience of the Patient and Public involvement and Engagement programme that changed the culture in the NIHR by linking progress to budgets and funding. Having inclusion explicitly defined and costed at the application stage, means we can fund research that brings us closer to our mission of reducing health inequalities.”

Now I strongly support this policy and in time I hope it will become embedded in research culture in the same way that recycling is almost second-nature now in many places. Inclusion is a fundamental necessity in research (see starfish leg #3). But culture is where the battle lies.

An organisation’s culture is the outworking of their values, beliefs and priorities. A company which values staff wellbeing and retention will invest resources in training for their managers in people skills, promotion opportunities, break rooms, and staff incentive schemes. Current examples of where this is working well could include Trader Joe’s, Bank of America and Octopus Energy. However, an organisation which values efficiency** and prioritises shareholder profits will focus their resources on cutting costs and driving up production. Staff are merely one resource amongst many (such as garment makers in the fast fashion industry) they are seen as a means to an end and can be easily replaced.

So it’s good that NIHR are insisting on PPI in research studies, yes? Well, yes, on the surface it certainly is. Making something mandatory means people will always be concious of it as a component in their research application, much as they are with needing ethical approval. But that doesn’t necessarily guarantee quality or consistency.

There’s a danger that PPI moves from being a virtuous/ethical/pragmatic thing to have (starfish leg #2) which means it has intrinsic value, to an inconvenient but necessary thing to have. The attitude might move from: “Well this seems nice, but I don’t have time to do it properly before the deadline in 3 days, so I’ll fudge something…” to requests from researchers saying: “I need six Romanians by next Tuesday”. Neither of these examples are great, but I’d suggest that the second option is worse. PPI is no longer an ethical imperative. It has become a commodity.

Jenni, Kate and I were discussing the potential commoditisation of PPI: the unintended consequence of making PPI mandatory, is that it becomes just another necessary component in the contruction of research. Instead of understanding and protecting the relational nature of public involvement in research, it becomes reduced to ‘some handy people in a room who give me feedback on my study because I need it’.

Again we see that that PPI is triggered by the researcher’s need*, not any kind of relationship between the researcher and their public partners. If PPI is provided as a service or a component to research, then there’s no need for any kind of relationship or reciprocity. It has become a commodity. And the danger is that without reciprocity, without a relational approach, PPI work cannot be sustainable. People might be enthusiastic about getting involved in or supporting research to begin with, but they don’t like being used, and pretty soon they start saying ‘no’ to invitations and requests and eventually there may not anyone at all who can help meet that mandatory requirement for inclusion and diversity (starfish leg #1).

So hopefully you can begin to see how all these things are interlinked, and why they need addressing with thoughtful and strategic care. (Also, it should go without saying that not all researchers view PPI as an inconvenience, obstacle or ‘nice to have but not necessary’ kind of thing. Just in case you were worried.)

And this is just one of the topics we were discussing.

I’d be really interested to know what you think about this PPI starfish and the issues we as practitioners are grappling with?

*I say ‘again’ because I know I’ve said this before in training sessions about PPI. I will try and add something about this in another post. Meanwhile, this is a quick extract from an interview I did with Rosalynn Austin on her Researcher Revealed podcast.

** I’m not saying that you can’t be people-focussed and efficient, however historically the focus has tended to be one or the other. You might find this podcast conversation between Simon Sinek and Walmart CEO Doug McMillon worth listening to.

Leave a comment