Image: https://emilypost.com/advice/table-setting-guides

It feels like it’s been a bit quiet on the research front lately, as I’ve been back in my PPI role and had less time for research activities. However, things are still pootling along in the background and I was finally able to meet with three more Patient Research Ambassadors to review the transcripts from the discussion groups which took place in August this year.

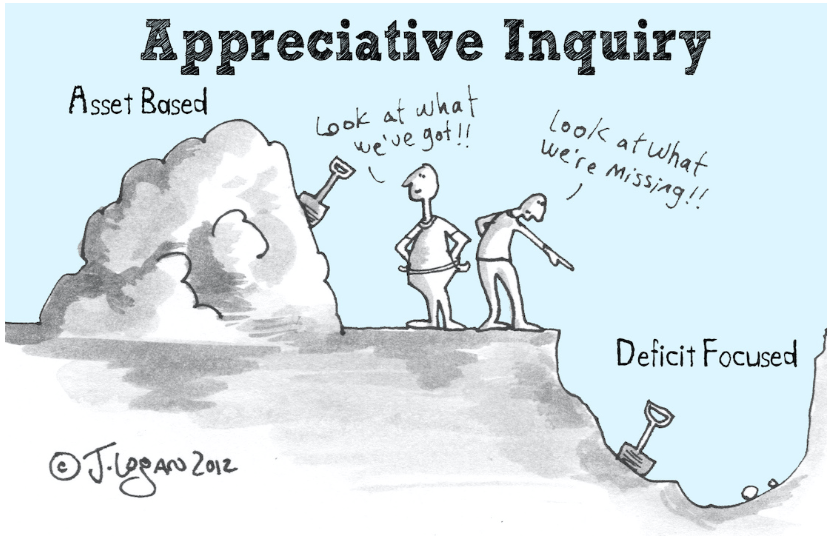

Jane, Alison and Simon ploughed their way through pages and pages of transcript text, which I am incredibly grateful for, and we met online to relfect on what we’d noticed…It was an incredibly diverse conversation, with different people noticing different things. One element was the topic of governance – not just governance structures for PPI work, but actually PPI as a form of governance or oversight. Medical research already has strict governance processes through the Health Research Authority (HRA) and the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Authority (MHRA) but it was an interesting insight to suggest that PPI could provide oversight from the patients’ perspective.

Another really interesting revelation was about culture…we were talking about the relationships and power dynamics between clinicians and the public, which I think might become established in medical school and then perpetuated through mentoring and practicing in the medical culture.

I asked if they thought the culture of the NHS had an impact on how clinicians perceive PPI in research? There was a brief pause before all three of them stated emphatically ‘Yes!’.

When you think about it, it’s kind of obvious? If some clinicians have a somewhat patronising or parent-child relationship with their patients, then naturally that will extend to their relationship with public contributors when they’re doing research. The attitude of treating patients and the public as equals will be harder to establish, if these same clinicians don’t view their regular patients as competant, capable individuals. It makes the whole ‘tokenistic’ aspect of PPI much easier to understand, when you take the culture of the NHS context into account.

As I’ve said before: not all clinicians hold a patronising view of their patients, and many more of the researchers I’m working with want to work in a person-centered way, with outcomes that will benefit their patients, which is really heartening for me as a practitioner.

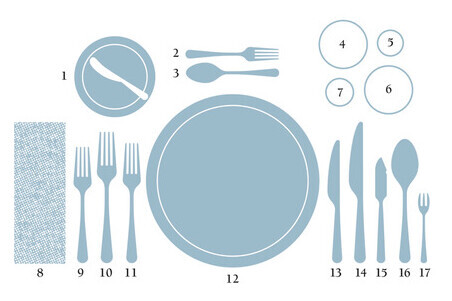

Anyway – how does all this relate to cutlery, I hear you ask?

Well – having done a very light touch scoping review, hosted three discussion groups and now taken a look at the themes raised in those discussions, my next step is to analyse it all and then arrange a meeting where everyone who’s been involved so far, can come back together and hear about what I’ve learnt. I’m keen to make this a collaborative journey, and I’m also aware that one of the biggest issues about research is that participants or contributors don’t get to find out the results of the study or what will happen next? This ‘gathering and discussion’ meeting will invite people to reflect on what I’ve learnt so far and offer their suggestions on what I might want to look at next? It makes this research project a shared learning journey – and it means I can benefit from the experience and perspectives of lots of different people* 🙂

*Of course, I might get totally overwhelmed with diverse suggestions from every corner, but I guess that’s the risk of being collaborative!

As I’ve been thinking through what and how I might share my findings so far, I’ve come up against a bit of a wall: I don’t yet know enough about research methodologies or analysis tools, to know what to do with the data I’ve got?? It’s like assembling a jigsaw puzzle but without having the picture. At the moment, I’m kind of responding to the data intuitively, and maybe that’s just how it works in real life research, but as I’m so new to it, I don’t know if I’m doing something wrong?!

It then occurred to me that research methodologies and analysis are quite a lot like cutlery: you need the right tools for the job! You need a soup spoon for soup, and an oyster fork for oysters**, but more than that, you need to know how to use the tools to make the food easier to eat. Think about Spaghetti Bolognese: a lot of people cut the spaghetti into small pieces, but Italians never do that. They simply hook up a few strands of spaghetti on to their fork, and then twirl it against the side of the bowl or plate until the fork has enough pasta on it, and then eat it. Yes, sometimes you might get the odd dangling piece, but if you don’t pick too much spaghetti in the first place and don’t overfill your fork, you can avoid messy slurping!

**Never felt inclined to eat an oyster. Therefore not likely to need an oyster fork anytime soon.

It’s not just about having the right tools for the job, but it’s also about recognising which tools will work best for you as an individual. Yes, I could undertake a systematic literature review as it’s a widely recognised form of research, but as someone with ADHD and a creative streak a mile-wide, I think that would be the death of me! However, creative analysis tools, or something like a narrative review, would probably work much better for me, and as a result, produce more valuable results which could be applied by other people more widely. Coming back to the cutlery analogy: if someone wants to eat a steak, but has a disability and can’t use a steak knife, then there’s no point in giving them one. A good pair of kitchen scissors would be much more practical and enable them to enjoy the meal as much as anyone else.

So I’m now on the lookout for research analysis tools which will help me understand the data I’ve got and how to make sense of it, so that I can explain that to the people who’ve been working with me, and use that learning and conversation as a roadmap for a Masters degree.

Easy-peasey?! 😀

If you have any suggestions for research analysis tools which you’d recommend or think I might find useful, please do drop me a line: authenticppie@gmail.com

Leave a comment