I’m going to preface this post with a disclaimer: I am not yet well-versed in the mechanics or philisophy behind research ethics. I think I have a general understanding of what ethics is and I can identify an action or behaviour which isn’t ethical. I have worked within faith-based and secular organisations and I’ve seen good and not-so-good examples of ethical practice in both those settings. Therefore, whatever I share in the post below is a reflection of my knowledge and understanding to date. There may be some very obvious answers to my questions. Or my questions may be new because I am new to this topic. Either way, it’ll be a learning experience!

So, I’m halfway through my Research Internship with ARC Wessex and whilst I’ve done a lot of work behind the scenes, I don’t feel like I’ve done any practical research. I have completed three, very good training courses (details on the Training and Resources page), attended a conference and created two academic posters, but I still haven’t done the activity I set out to do, which is the informal conversations about PPIE. Or ‘PPI on PPI’.

In addition to the activities above, I have written a protocol for my project as well as a Participant Information Sheet and a Consent Form. For those of you who don’t know, these are guidance and permission documents which are an essential part of research.

The protocol is essentially the handbook of what the study is all about: the background and context, aims & objectives, inclusion and exclusion criteria (who will take part and who can’t), who’s responsible if things go wrong and what will happen afterwards.

The Participant Information Sheet or PIS is a simplified document for potential participants which explains what the project is all about. It explains why they’ve been invited to take part, what the benefits and risks might be, what they’ll be asked to do, what kind of data the study will be collecting and how that will be used and stored.

The Consent form is the final part of that package and links closely with the PIS. It breaks down the PIS into sections and the potential participant will go through that form and check off whether or not they are happy to proceed with each of the statements laid out in the form.

Both the PIS and Consent form have to be written in Plain English so that people who are thinking about getting involved in research have a clear idea of what they’re being asked to do and why. It would be unethical to ask people to get involved in a study without them understanding the implications and potential risks of what they’re being asked to do.

A bit of background…

The principle of this process can be linked back to the Hippocratic Oath, where a physician “pledges to prescribe only beneficial treatments, according to his abilities and judgment; to refrain from causing harm or hurt; and to live an exemplary personal and professional life.”

The Nuremberg Trials which took place between 20 November 1945 and 1 October 1946 brought this into sharp focus. The trials covered a number of different aspects including prosecuting individuals and organisations. There were several different aspects to the Nuremberg Trials as the breadth and scale of atrocities during World War II meant that the topics had to be broken down into different sections. The Doctor’s Trial focussed on the medical experiments that prisoners of war were subjected to. These experiments were varied and cruel and included: tests on hypothermia, the effects of altitude and oxygen deprivation, sterilization, removal of nerves, muscle tissue and bone, and intentional use of salfinomide, mercury and infection with typhus and malaria. All of these experiments were carried out without anaesthetic or follow-up treatment afterwards.

As a result of the Doctor’s Trial, the Code of Nuremberg was established, with ten ethical principles under which experimentation on humans could be permitted. The first principle states:

The voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential. This means that the person involved should have legal capacity to give consent; should be situated as to be able to exercise free power of choice, without the intervention of any element of force, fraud, deceit, duress, over-reaching, or other ulterior form of constraint or coercion, and should have sufficient knowledge and comprehension of the elements of the subject matter involved as to enable him to make an understanding and enlightened decision. This latter element requires that before the acceptance of an affirmative decision by the experimental subject there should be made known to him the nature, duration, and purpose of the experiment; the method and means by which it is to be conducted; all inconveniences and hazards reasonably to be expected; and the effects upon his health or person which may possibly come from his participation in the experiment.

Hopefully now the protocol, PIS and Consent form I explained earlier make more sense in the context of that information.

The steps of ethical approval

Ethical approval in healthcare research is granted by an external Ethics committee or panel, who will review the protocol, consent form & PIS along with an ethics application form which explains what I want to do and why, and why I’m seeking their permission to proceed. The panel is made up of a mixture of ‘lay people’ (members of the public) and medical professionals. It’s a good process in terms of transparency and accountability and the Ethics committee (in clinical research it’s called a Research Ethics Committee or REC) can request further information or clarification on a study, or they can refuse permission altogether.

Ordinarily, if I’m doing PPI/PPIE work with an existing Patient Research Ambassadors (PRAs) group or PPI group – in other words a focus group talking about their opinions or perspectives about a research study, I don’t need to seek ethical approval. This is actually a regular part of my job and ethical approval isn’t required because people are just sharing their opinions, not personal data.

However, if I wish to write and publish a paper about those conversations then I do need ethical approval because I will be using the content of those conversations for a piece of work beyond the scope of the PPI conversation. Participants in that conversation have the right to know how their comments will be used, whether they will be identified in the paper and what will happen to their data afterwards.

So far so good. Now this is where it starts to get interesting…

If I’m recruiting members of the public into a research study I need ethical approval, but not if I’m recruiting NHS staff or other professionals. In that case, I would need approval from the Health Research Authority (HRA) approval but not ethics. NHS Staff doesn’t appear to trigger the ethics process because they’re professionals and should apparently already know enough about research to make an informed decision about whether or not to take part.

My issue with this is that NHS Staff are also members of the public. So are they not entitled to ethical protections? Does it depend on whether they’re being recruited because they’re a staff member? What if they’re not part of the research team or know nothing about research – how can they make an informed decision? Also, what if a member of the public is a retired clinician? Arguably they might be better placed to make an informed decision about getting involved in a research study, than someone who works as a clerk on the Medicine Ward? Maybe I’m misunderstanding it, but it seems a bit odd.

Another puzzle I have about ethics and ethical approval is that it seems that ethics assumes that patients have no prior or relevant knowledge and therefore can only operate within a very specific set of parameters. They cannot contribute to the study beyond being a passive participant. They go where they’re told and do what they’re told but they don’t have any agency to change anything or offer suggestions. Aside from the obvious problem of changing a study part-way through and thereby screwing up data collection and the validation of results, this appears to be an area where we’re missing a trick, because patients and participants DO know things and may well have relevent information or prior experience to contribute*, but they’re not being asked and it can’t be included once the boundaries of the study have been set.

If a decision is made by the study team that they need to make a change or an amendment as it’s technically called, then the study has to be paused and another submission made to the REC (ethics committee) in order to get permission to proceed but with the new change in place. Even the wording for posters or thank you letters have to be signed off by the HRA and REFC before they can be released, and you’re not allowed to edit the wording afterwards otherwise it could be interpreted as coersion of potential participants.

*The argument here will be that this is where public involvement comes in, as part of the study design, but in a lot of cases PPI comes at a point where the study is already written and fully-formed. At this point, PPI is more like to be ‘engaged consultation’ rather than impactful involvement, although this can vary depending on the research lead and their team.

Now, in an ideal world, we would have participatory research where patients and clinicians work together collaboratively to research issues and solve problems. However, this is where the current ethics framework can trip us up, because it assumes that the various people in the study only hold one role. A researcher can only hold the role of researcher and a participant can only hold the role of participant. The authority (power), capability (the extent of someone’s ability to understand or manage a task), and culpability (who’s legally responsible) are very carefully delinianted (separated out) between the different roles of participant, researcher or study support (such as a Pharmacist or Data Analyst) and you can’t move from one to another – even if you have skills in any of these other roles or areas. And, as I said before, any changes in the study have to be sent back to the Ethics Committee to get signed off before they can be implemented.

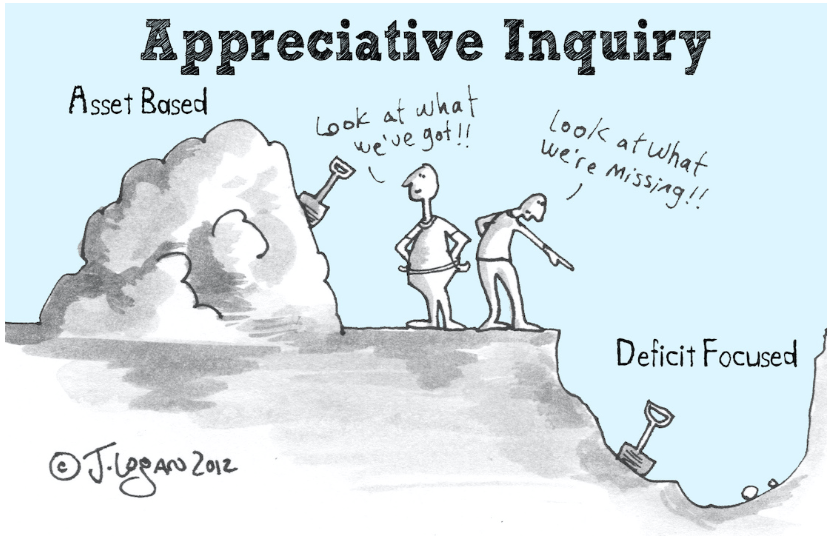

Now, don’t get me wrong: I think ethical principles and practices are incredibly important – they are the boundaries which keep people safe; the transparency and accountability which can anticipate and prevent harm to patients and wasteful use of resources. But I’m also starting to think that some of our ethical principles are based on assumptions such as “the clinician or researcher’s knowledge is automatically superior to the participant”. It places those two people in a very unbalanced power dynamic, similar to that of a parent and child, where the parent has all the agency and the child has none. The ethics process is meant to keep participants safe, which it does, but it also constrains and limits their ability to contribute beyond the very specific parameters of the study.

I think there’s an assumption somewhere that when it comes to ethics and research ‘one size fits all’ and I really don’t think that’s true. I hear similar frustrations and reflections from colleagues within universities and I think if I have the opportunity to do further research, I am going to crash headlong into this issue.

I don’t want to work in a way which leaves research participants (or indeed myself) vulnerable to exploitation, coercion or bad practice. But I do want to work with people in a way which is equitable; in a way in which power is shared evenly and appropriately and in so doing, knowledge can be generated from a range of sources which reflects and values those different starting points.

The ethics of ethics is something which I’m only just beginning to explore, but I have no doubt I’ll be coming back to it…

Leave a comment